The following is a little synopsis of how government intervention caused the financial crisis. None of this is new. I’ve just synthesized several ideas into a one story, that I think captures and explains the main elements of the crisis.

The conventional story of the financial crisis is that it is an example of capitalism gone awry. Large corporate bonuses created a moral hazard problem whereby the people who ran large investment firms cared more about short term profits than the long term viability of their organizations and therefore made a bunch of risky decisions. In this story, the other players, home buyers, investors, creditors of large institutions were unable to take care of their own money and so, for some reason, the normal checks and balances of a market failed. Both mechanisms lead, logically, to the conclusion that more oversight and government regulation of banking and finance is required to prevent future crises. This is a coherent story, but it’s not accurate. It is, in fact, the unintended consequences of government regulation and intervention into the economy and the world of finance that are largely responsible for the Financial Crisis of 2008.

In order to account for the causes of the crisis, there are two key questions that we have to answer. First, what caused housing prices to skyrocket during the late 1990s and early 2000s? Second, what factors help explain why commercial mortgage originators, government sponsored entities (GSE’s), and larger investment and commercial banks and their creditors made bad/risky decisions involving the purchase of mortgage backed securities. In other words, what forces were responsible for funnelling these investments into the banking system?

The Housing Bubble

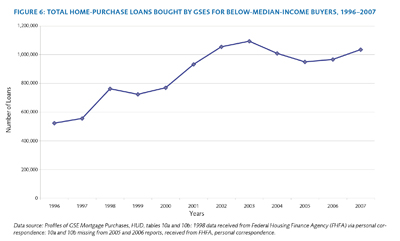

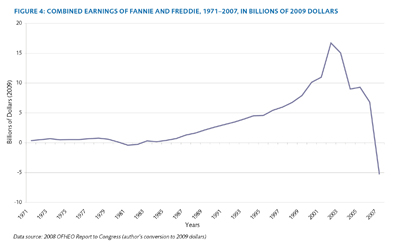

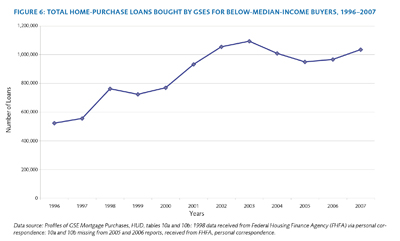

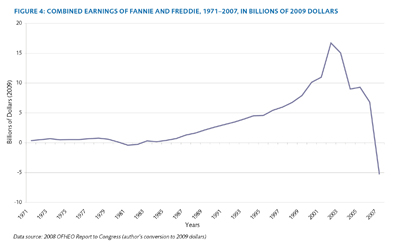

The housing bubble, unsustainably high housing prices, was caused by an increase in the demand for homes. This demand was fed by two government policies: first, the National Home Ownership Strategy that actively sought to use government policy to increase homeownership, especially among the poor. In the late 1990s, the democrats decided that poor people should get houses. They leaned on government sponsored entities (GSEs), Fanny Mae and Freddy Mac, to buy loans from commercial lenders that gave mortgages to poor people; even if the recipients were not the most credit worthy individuals. They did. And this allowed lots more people to enter into the housing market, which drove up the price of housing. The GSE’s not only bought mortgages, but they sold securities to investors of various sorts. The security was, basically, that investors who bought MBS’s were protected from the potential downside (to some degree), because the GSe’s would take back mortgages that went bust. Second, the low interest rate policy undertaken by the U.S. Federal Reserve: this basically made credit cheaper, and so more people could afford houses, and also bigger houses. Of course, the price of credit was lower than the market price for credit, there was a shortage and this caused interest rates to rise – and a lot of investments (especially housing) became way more expensive.

These two factors combined to massively increase the demand for housing, and therefore, the price of housing. It was a bubble because the price increases were sort of based on artificial factors: poor people who should not have had mortgages AND a price ceiling in the market for loanable funds, which led to a credit shortage and massive interest rate hike, and eventual correction in the housing market.

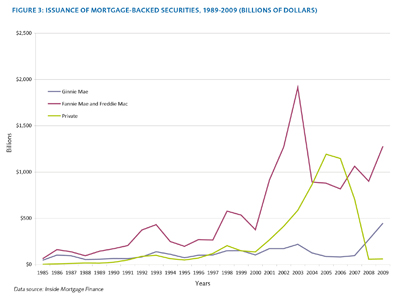

Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) and the Banking System

Why were mortgage assets funnelled into the banking system in such a manner as to cause a large scale crisis?

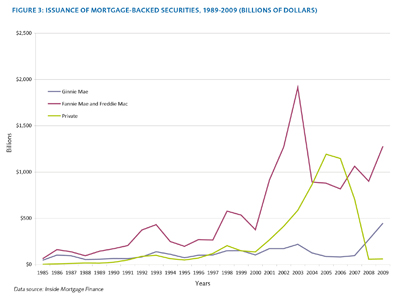

The first reason is capital control regulations. Basel I internationalized and standardized capital regulations, which specified a bank’s regulatory capital level by the ratio of capital divided by the risk adjusted value of a bank’s assets. Risk adjustment was performed by grouping assets into various categories, each of which were rated differently. Really safe assets like gold and government bonds were assigned a 0 percent weight; GSE obligations were weighted at 20 percent; mortgages were 50; and all other assets were weighted at 100 percent. Under this scheme, a bank originated mortgage would count as 50 percent; but if it was securitized, it would be worth 20 percent; holding securitized mortgages, which held a high return, would also have the advantage of freeing up; significant capital which could then be used to make more investments. If bankers didn’t care about risk, then they could have held assets with lower ratings that would have yielded higher returns; the main goal of buying MBS’s, then, was not safety, or yield, but capital relief. This was, in turn, a function of the regulatory structure of the financial system at the time.

In other words, the main reason that banks bought lots of MBS was in order to comply with a capital requirement regulations set down by the Basel I accords. These regulations essentially funnelled the overvalued capital created by the housing bubble into the banking system.

Government intervention also led to moral hazard issues that exacerbated the risky borrowing and lending practices of key actors, although this was probably not a decisive cause of the crisis. Commercial mortgage initiators also had an incentive to make risky loans. Because of government housing policy, they could sell bad mortgages to the GSEs. The GSE’s bought mortgages and then packaged and sold them as securities to banks and other investors. This had the effect of “offsetting” the risk associated with these loans, and it essentially answers the question of why mortgage lenders would make such terrible lending decisions.

But investment banks also bought lots of MBS. And they bought them with borrowed money, and their creditors continued to lend them money: the question is not so much why investment banks would buy these securities. They were basically encouraged to by the capital regulations under Basel 1, which had the effect of pushing the housing bubble into the financial system. The bigger puzzle is: why would creditors, who gained NOTHING from the risky behaviour, continue to make loans to these highly leveraged institutions?

This is where the “too big to fail” policy comes into effect. The U.S. government had repeatedly rescued creditors to the tune of 100 cents on the dollar. There is some evidence to suggest that creditors knew this in advance.

Conclusion

Was it all about “large bonuses”? Probably not. If that was the case, we’d expect banks to act more risky – purchasing lower rated assets that yielded higher returns. However, bankers clearly had a preference for capital relief, not yield.

Was it about irrationality? Yes and no. Uncertainty is a regular part of economic life. Unregulated investors who were not bailed out did by MBS. But, overall the regulators did a worse job than the private sector in picking winners. We can see this by comparing the regulated and unregulated sectors of investment and finance. “U.s commercial banks chose the safest, lowest yielding MBs-agency bonds- twice as often as AAA-rated private label MBS, which paid higher yields; and nearly ten times as often as even higher yielding AAA CDO”. This clearly shows that bankers were not sacrificing safety for revenue.

Overall, the lesson of the Financial Crisis is that well intentioned government policies have unintended consequences. The government’s desire to give poor people houses created a bubble – that was ultimately unsustainable. It may have been a relatively minor event had not these assets been pushed into the banking system by other well intentioned policies, namely, capital regulations. Finally, by subsidizing risk at various levels, government policies countered the natural market checks and balances that might have otherwise mitigated or tempered the decisions of private sector groups that ultimately led to the crisis.